England

by Kenta Takeshige

The East India Company (EIC) was established in England in 1600. This was followed by the establishment of the East India Company in the Netherlands in 1602 and in France in 1604. At that time, "East India" referred to a wide area that included East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian continent, Southeast Asia, China, and even Japan. Each of these East India Companies was a joint-stock company that was granted letters patent by their kings and had a monopoly over the Oriental trade of their respective countries. Although it was a pioneering organization of today's stock companies, its scope of activities included colonial management, and even military activities with own army were permitted. The East India Companies of each country repeatedly fought each other as they competed for concessions and colonies in the Oriental trade.

Oriental lacquerware introduced by the British East India Company received an enthusiastic reception, leading to the development of imitation lacquerware "japan" and lacquer imitation manufacturing technique "japanning".

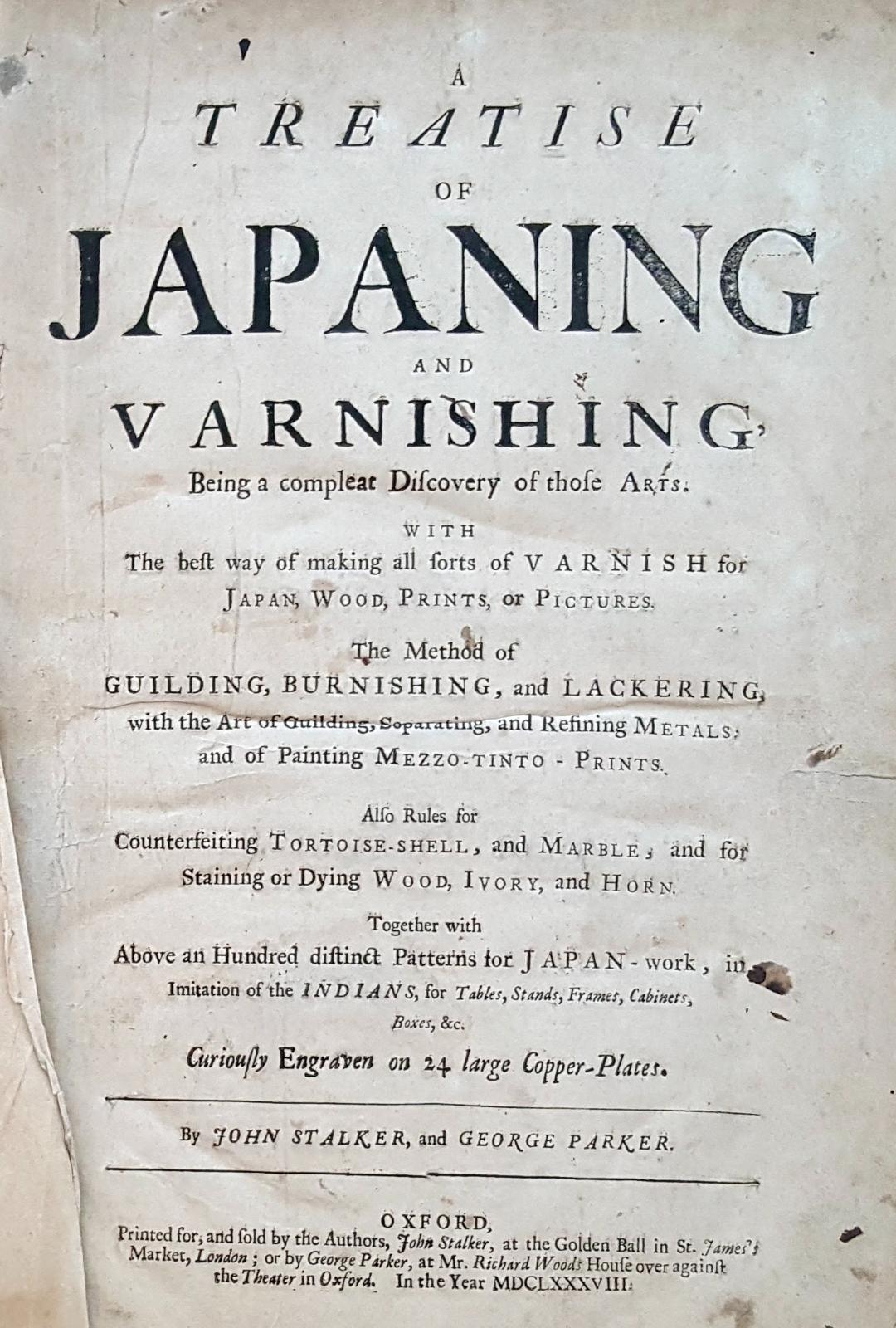

The book "A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing" by John Stalker, George Parker, Oxford, 1688 (Alec Tiranti Ltd, 1998 reprint) was published in Oxford more than 300 years ago, but it is still very popular today. It is the bible of lacquer technique manuals, which has been the most read book ever. A collection of 24 designs is included at the end of the book.

‘In this book, the authors mention the differences between Japanese lacquerware and reproduction lacquerware, and recognize that what they are trying to create is an imitation.

It is stated in the text that it would be good if the meaning will be evaluated: because it is impossible to make Japanese lacquerware, but if they use the best materials they can obtain, improve their techniques, and make something similar to Japanese lacquerware, they can demonstrate their efforts and skills.’ 1

The purpose of this publication was not to make it impossible to distinguish between genuine products and fakes, but rather to treat materials and manufacturing methods as open resources, which is of great significance.

After this book was published, it quickly became popular and a few chapter’s of Stalker & Parker's work were copied by William Salmon2 - those who followed - and had been reprinted and revised.

So, why did the authors of this book take the move to publish and share the know-how with everyone, rather than registering the japanning recipes as a trademark and monopolizing it?

Regarding this, art historian Hender Delves Molesworth said as follows in the 1960 reprint of Alec Tiranti's edition:

‘No details are known about the authors of this book, John Stalker and George Parker. However Molesworth speculated that judging from John Stalker's London address, he was probably a furniture maker involved in japanning, or someone who run such a company, while George Parker's address was in Oxford, so he could be a member of Oxford University. He may be a related person or a researcher (though no trace of him has been found at the university so far). In other words, at the time, both craftsman and researcher felt a strong need to publish a technical book on japanning.’ 3

It is thought that when the production of imitation lacquerware began, inferior products were also on the market. Therefore, the emphasis was on improving the bad production of the industry as a whole and raising the level of the bottom. Cattersel elaborates on this further as follows:

‘However, this does not necessarily mean that the japanning industry had a bad reputation. Japanning was performed in low(er) circles for an income and higher social circles as leisure activity. The lower circles did had limited means to acquire proper tools and raw materials and therefore likely produced inferior lacquerware. On the one hand the production of the former resulted in inferior quality objects but on the other hand, these objects were not expensive and thus within reach for the lower middle class, resulting in availability for nearly all social classes. Additionally, Stalker & Parker's remarks on the "inferior" quality of European lacquer could also be a move of patriotism. Although this might be read as a paradox, it calls for action for the reader, to buy and use Stalker & Parker's treatise and ignore other sources of knowledge on this topic. And from a social point of view, it was about raising the pitchforks and uniting to create products of value that could compete with the constant influx of imported lacquerware, avoiding the eastern flow of orders, and returning the results to local artisans.’

Rise of furniture designers

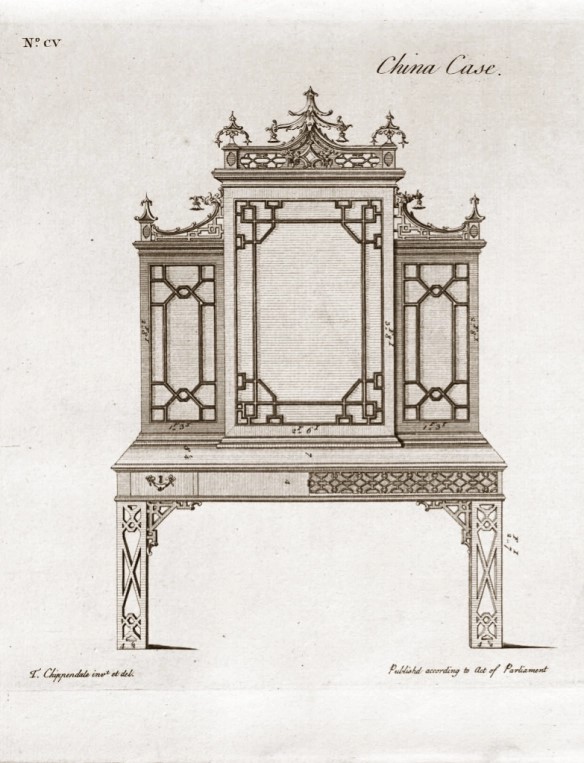

A significant change can be seen in the 18th century in the field of furniture production. Until that time, it was furniture makers/craftsmen who produced high-class furniture under the name of the kings. However, from the mid-18th century onwards, people who could be recognized as the prototype of modern "designers" emerged and were active in aristocratic society. Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779), George Hepplewhite (1727?-1786), brothers of Robert Adam (1728-1792) and James Adam (1732-1794), Thomas Sheraton (1751-1806), leading figures in the history of British furniture created designs under the names of individual artists. What these furniture designers have in common is that they published furniture design catalogues and developed their own unique styles. Thomas Chippendale included 160 furniture design drawings in his book "The Gentleman & Cabinet-Maker's Director". Some of his design drawings showed cabinets with Chinese tastes and screens incorporating lacquer panels. These were lacquered oriental-style furniture in a style called "chinoiserie".

Furthermore, lacquer was explored for applications other than furniture.

In the 1660s, Thomas Allgood (c.1640-1716) of Northamptonshire was appointed manager of Pontypool Ironworks. Allgood developed Pontypool's japanning process, which could allow metal plates to be treated in a way that produced lacquered and decorative finishes.4

Thomas Allgood died in 1716, having been unable to commence production of his Pontypool lacquerware, but his sons established a japanworks in Pontypool by 1732. They succeeded in baking lacquer on metal at 300-320 degrees, and lacquered metal-ware called "Pontypool Ware" was produced. Teapots and kettles including decorative bread baskets, tea trays, dishes and other items were manufactured in response to the growing tea culture. This baking technique was used even at low temperatures and was applied to painting papier-mâché.5 The lacquered papier-mâché model became increasingly industrialized and was produced until around 1930.

-

Quote: John Stalker, George Parker, "A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing", Oxford, 1688 (Alec Tiranti Ltd, 1998), translated by Itani Yoshie, 「漆への憧憬 ~ジャパニングと呼ばれた技法~」井谷善恵 (翻訳) 里文出版, 2010. Pg. 170. ↩

-

William Salmon, and P. Holmes. "Polygraphice, or, the Art of Drawing, Engraving, Etching, Limning, Painting, Washing, Varnishing, Colouring, and Dying", 1672. ↩

-

Quote: John Stalker, George Parker, "A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing", Oxford, 1688 (Alec Tiranti Ltd, 1998), translated by Itani Yoshie, 「漆への憧憬 ~ジャパニングと呼ばれた技法~」井谷善恵 (翻訳) 里文出版, 2010. Pg. 172-173. ↩

-

Willem Kick was already lacquering metal plates at the end of the 16th, beginning 17th century and he obtained this technology patented. At the same time, there was the Meissen production - that not only created the famous Meissen porcelain - but also black lacquered metal commodities; or the lacquered Böttger wares. ↩

-

Papier-mâché is a formative technique that involves pasting paper or other material onto a frame made of bamboo or wood, or a mold made of clay. Most of them are hollow and light compared to their appearance. ↩