Japan

by Kenta Takeshige

In Japan, lacquer is called Urushi 漆.

Lacquer trees Urushi no Ki are believed to occur naturally in Japan. Lacquer has been used since the Jomon period. By this time, people discovered the adhesiveness and protective power of lacquer and used it to strengthen and safeguard weapons and tools.

A masterpiece of ancient Japanese lacquer art made during the Asuka period is Tamamushi no Zushi (玉虫厨子), exhibited at Horyuji Temple. The technique "Makkinru" on Kin-Gin Denkazari no Kara-Tachi (金銀鈿荘唐大刀), which was handed down to the Shosoin-Treasures of the Nara period, is believed to be linked to the origin of "Maki-e" in Japan.

At the same time "Raden" was imported from the Tang dynasty.

%20%C2%A9%EF%B8%8ENara%20National%20Museum.jpg)

%20%C2%A9%EF%B8%8EShosoin%20Office%20Collection%20%E6%AD%A3%E5%80%89%E9%99%A2%E4%BA%8B%E5%8B%99%E6%89%80%E8%94%B5.jpg)

※ There are various theories and arguments that these two famous works; Tamamushi no Zushi & Kin-Gin Denkazari no Kara-Tachi, were produced in foreign countries and imported into Japan at the time.

Medieval times

Japanese culture flourished during the Heian period. The Japanese sense of cherishing the beauty of nature and celebrating the seasons brought to life the Maki-e technique that enables those delicate expressions. In addition, high-precision metal powder manufacturing technology supported advanced Maki-e works.

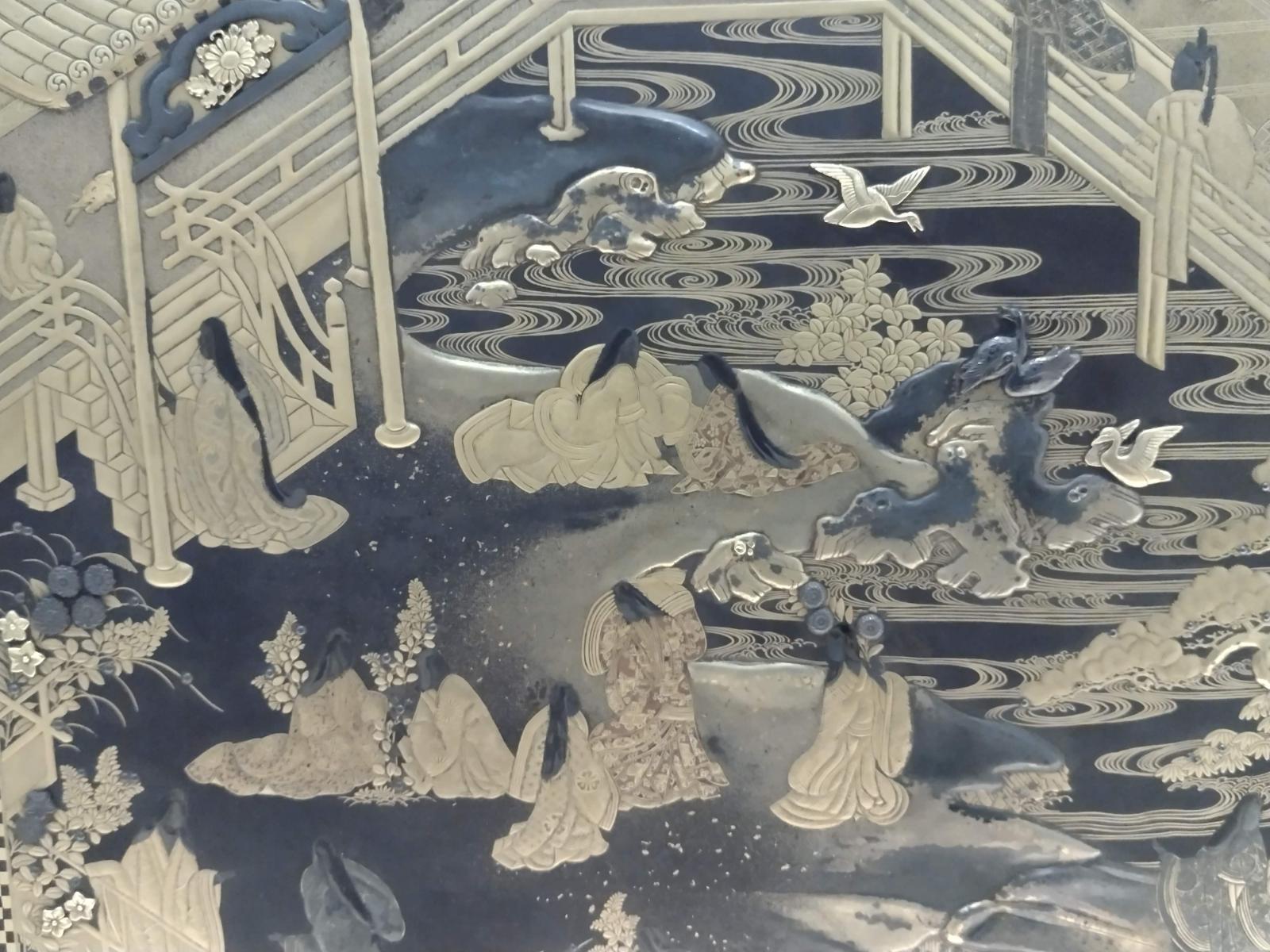

During Heian period, "Togidashi Maki-e" was invented, developed and completed. In the latter half of this period, "Hira Maki-e" was also produced. In the Kamakura period, carved lacquer "Tsuishu" was imported from Song dynasty and imitated through "Kamakura-bori", which instead of carving the lacquer, sculpts the wooden base. After the technique of Hira Maki-e was perfectioned, "Taka Maki-e" appeared. During the Muromachi period, the "Chinkin" technique was imported from Ming dynasty. Around this time, the most difficult Maki-e technique, "Shishiai Togidashi Maki-e" was born. During the Azuchi-Momoyama period, the lacquer industry grew rapidly due to trade with Europe, and Nanban lacquerware for export was produced using plenty of Raden and Maki-e techniques. In the Edo period, the development of particular lacquer technologies in specific areas was a booming industry and encouraged by the feudal system. Distinctive local lacquer technologies in different parts of Japan are still typical nowadays. Despite the isolation policy during the Edo period, some goods such as lacquerware were nevertheless exported by the Dutch.

Modern to present

After World War II, Japanese lacquer art faded away with the passage of time. In general the demand for domestic lacquerware has decreased but today the country is trying to promote lacquer art once more. It is encouraging to see a new generation of young artists taking on lacquer art as another way of expression rising.

It's been a while since we've heard the term "Digital Crafts," which refers to the fusion of traditional craftsmanship and digital technology through the use of digital devices. Lacquer art is no exception. There's no doubt that we're living in an age where craftsmanship requires evolution.

3D printer: Create a substrate for lacquer art, or use this base for plaster molds, etc.

CNC router: A woodworking router obtains data information and produces woodwork.

Laser cutting: Cutting out decorative patterns for Raden, mother-of-pearl technique.

Another concern is that Japan came to depend upon China for the import of lacquer required for lacquer work. Efforts are made though to plant lacquer trees, harvest and distill lacquer sap again domestically.

~Maki-e techniques~

(Quote from Glossary of Urushi Terms, “Project for Conservation Works of Japanese Art in Foreign Collections I” by Tokyo National Research Institute of Cultural Properties, 1998)

Togidashi Maki-e: designs are drawn with lacquer and Maki-e powder is sprinkled on them. Then, after the lacquer has dried, another layer (or layers) of lacquer is coated over the surface which is then abraded with an abrasive, such as charcoal, until the design is revealed. Then the surface can also be polished.

Hira Maki-e: designs are drawn with lacquer and Maki-e powder is sprinkled on them. Then, after the lacquer has dried, the powders are fixed in their place with lacquer. The design is then polished to a gloss with fine stone powder.

Taka Maki-e: lacquer or lacquer foundation material is used to raise designs. Gold or silver powder is then sprinkled on the surface to highlight the patterns.

Shishiai Togidashi Maki-e: lacquer or lacquer foundation material is used to raise patterns. Then Maki-e powder is sprinkled on the surface. This is followed by coating lacquer over the entire surface. Finally, an abrasive such as charcoal is used to abrade the surface and reveal the design which can then be polished.

Keshi (-fun) Maki-e: a simplest Maki-e technique in which patterns are drawn with lacquer and Keshi-fun powder is rubbed on gently with silk wool. After the powders have been fixed, they may be finished without burnishing.

Kintsugi

History of Kintsugi

"Kintsugi" is a technique for repairing ceramics and lacquerware using lacquer that has been handed down from ancient times. Jomon period pottery may show traces of repairing the damaged part with lacquer, which can be considered as a primitive Kintsugi.

There is a bowl called 馬蝗絆 (Horse Locust Bond). This bowl was given to Taira no Shigemori by his Chinese colleague in the 12th century. After that, it became the property of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa in the 15th century during the Muromachi period. Yoshimasa found cracks in the bottom of the bowl, so he sent it to China requesting a replacement bowl. As there was no such excellent celadon bowl in China any more, they stopped the cracks in the bowl with staples and sent it back to Japan. The staples struck in this bowl are like huge locusts. The Shogun was very pleased to receive the repaired bowl. In Japan at that time, Maki-e already existed, so the repair method was replaced with Japanese style using Urushi & Maki-e.

The artistic value of Kintsugi has been cherished by Tea Masters who accepted the repaired ceramics as they are: visually damaged but still fully functional. Later Tea Masters started to pursue the beauty in Kintsugi: artistic and aesthetic value increases through repairs. The biggest feature is to enjoy the scars as a scenery by decorating the seams with gold, silver, or vermilion lacquer, etc. Instead of making it intact, accept its history and create a new harmony.

Different methods or approaches in Kintsugi

If you have all the broken pieces, of course use them all. This is called "Tomo-tsugi", Joint of Origin. Kintsugi using pieces of ceramics that are different from the main body is called "Yobi-tsugi", Joint by Call. There was a time when this Yobi-tsugi was also used as a symbolic wedding gift: since different pieces are combined, a technique to bond them well is absolutely necessary.

Lacquer as a Kintsugi material

The Kintsugi technique takes advantage of the many properties of lacquer. It has many uses, including repairing cracks, filling gaps, patching missing parts, and gluing broken parts. For this reason, lacquer is used as a finishing material and as a base for metal powders and other materials. Lacquer can be used on its own as an adhesive, but it is also mixed with other materials such as wheat flour, rice flour, earth, or clay to form a paste. In this way, lacquer is used as an adhesive and filler.

Each process of Kintsugi is short, but it may take several months to complete one Kintsugi object because it takes time to harden. Lacquer attaches well on wood, bamboo, textile, paper and leather, but it does not easily stick to glass or metal, so an additional process such as "Yaki-tsuke", baking process is required.