Japanning

by Kenta Takeshige

Overview Japanning

Lacquerware, which was brought from East Asia at the dawn of the Age of Exploration, greatly fascinated the people of Europe, prompting them to try to make it with their own hands. The reason for this was, in addition to a fascination with the Orient, the lacquerware imported from China and Japan at the time were extremely expensive, and even though they were ultra-luxury items, demand far exceeded supply. Asian lacquer exhibits excellent resistance to water, relative high heat, alcohol and other chemicals. Such material properties were not known by western societies. This is why at least in part- the West was so interested and invested in this product. It has unique properties- almost mythical properties- and having such raw materials available in the West was highly desirable. But Asian lacquerware is made from materials that could not be obtained in areas of Europe; due to being made from the far eastern lacquer trees which didn't grow in European climate, and export restrictions by the East (lacquer was forbidden to be exported). Either way, the material’s properties of hardening through oxygen and moisture, made it almost impossible to export it to the West (Asian lacquer sap hardened during the long voyage and was no longer usable by the time it arrived in Europe). Finally, the manner of curing this product in a temperature & humidity adjusted/acclimatised chamber was not fully understood here in the West. Furthermore, it is hard to understand not only the raw materials, but also all the complex production processes of various lacquer techniques, which must have continued to be a mystery of the East. Thus, this forced the West to search and develop their own technology to recreate the aesthetical aspects of eastern lacquer.

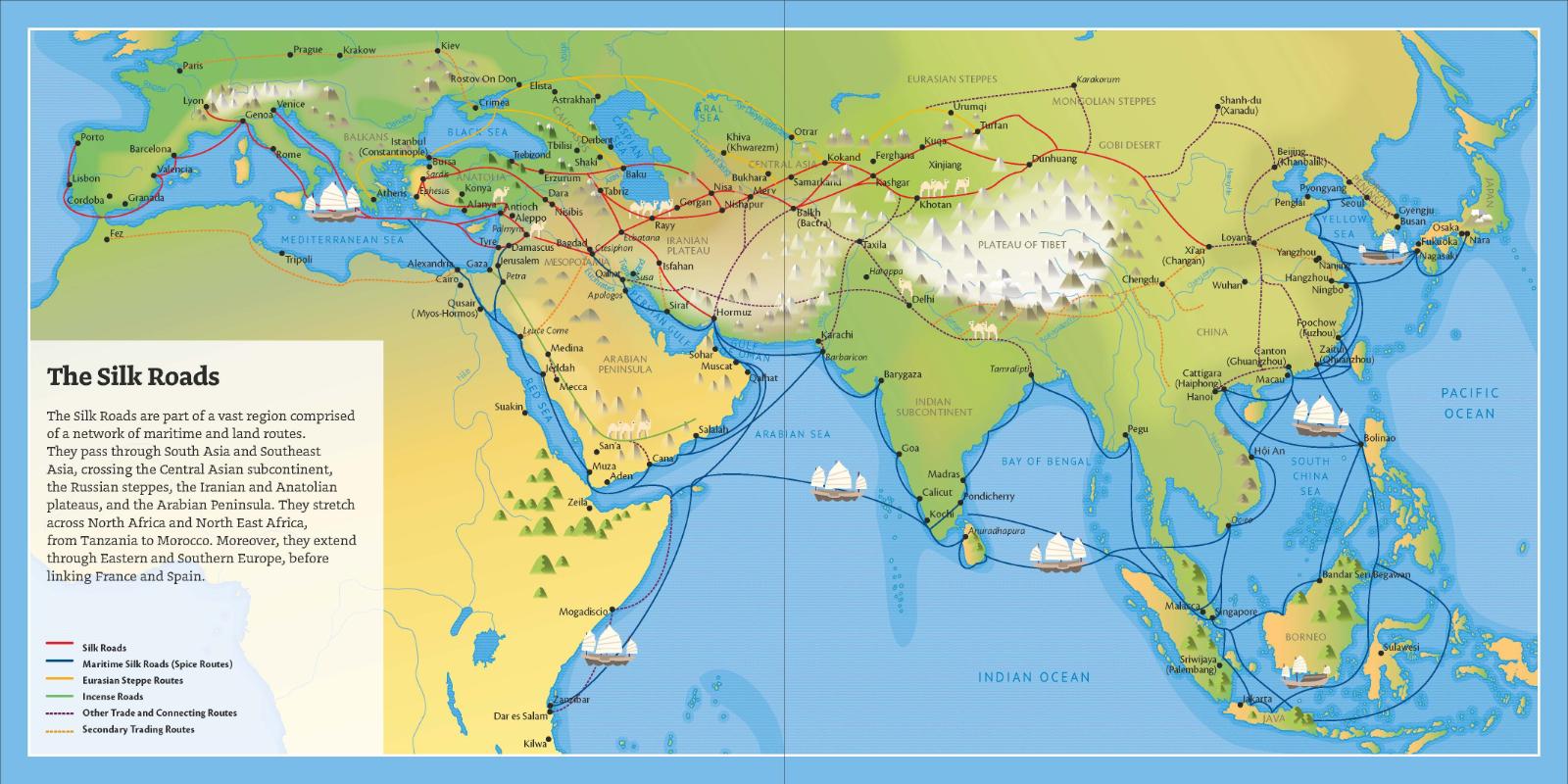

The technique for making imitation lacquerware is generally called "japanning", suggesting its origin from Japan. In addition, it is called by various names depending on the country and region, such as "Japanning" in English, "vernis" in French, "la vernice cinese" in Italian, "sinees lakwerck" or "chineese vernis" in Dutch, and "indianish werk" in German. The purpose of japanning is to faithfully imitate Oriental lacquerware using substitute raw materials and technology available in Europe. The japanning technology was based on the lacquer manufacturing methods widely practised in Islam began in the16th century, reached a considerable level by the end of the 17th century, and achieved its golden age in the18th century. The lacquers used in japanning were made from materials available in Europe as well as those imported from various regions in Africa, South America, and Asia, such as sandarac, copal, shellac, and linseed oil, etc.

These lacquers have a slight yellowish tint and are transparent. By adding colourants/pigments such as white, red, yellow, and blue to these, lacquers with good colour development are completed. In principle, add pigment to the first layers and gradually reduce the amount of pigment to zero. The reason is that pigments are particles, and particles disrupt the surface of varnish/lacquer, not allowing it to create a perfectly smooth surface. Therefore, the presence of pigment particles (whether pigments or dust) on or near the surface of the final coating is undesirable.

High colour development and glossy surfaces were characteristics of lacquers at the time.

And to make black lacquer, colourants/pigments such as bone black made from burnt bones and horns, ivory black made from burnt ivory, and lamp black made from candle soot were mixed into the lacquer medium. Bone black is black when baked, but turns black with a slight brownish hue when powdered. Ivory black becomes a glossy black lacquer, but it requires expensive imported ivory to be burned into powder. Black pigment made from expensive ivory was not an easy colouring material to use.

In lacquer mixed with soot, the soot has a low specific gravity and floats on the lacquer surface, resulting in a lack of gloss. To resolve this issue, adjust lacquer medium at the right viscosity to allow for the soot particles to remain suspended in the medium.

In fact, the best black was soot black; because its particle size is extremely small compared to ground bone or ivory black. This is beneficial for making smoother ground layers.

Japanning materials

※ The japanning materials are summarized and introduced here. However, the perception of raw materials collected from around the world has changed over time, and the names, materials, and types often do not match completely, leading to misunderstandings and confusion.

Common materials for japanning

Sandarac is a resinous substance collected from the Sandarac gum tree Tetraclinis articulata, a tree species of the Cupressaceae family, and used as a binding medium by dissolving it in a solvent (ethanol, ethyl alcohol). It is native to the Mediterranean region, particularly in parts of the Atlas Mountains in northwestern Africa, southern Morocco. Resin naturally oozes from tree trunks, but it can also be obtained by cutting into the bark. It hardens on exposure to air and is distributed in the form of small translucent yellowish solid chips.

Shellac is a binding medium made by dissolving the secretions of the female lac insect Kerria lacca also known as Laccifer lacca, which lives on trees in the forests of India and Thailand, in alcohol. It can be purified and the reddish colourant removed to obtain a yellowish/transparent medium. The secretion, called sticklac, is scraped from branches, ground and dried and then filtered through a sieve to remove impurities. The sieved material is washed repeatedly to remove impurities, resulting in seedlac. If seedlac is further purified by heat treatment, a pure shellac is obtained, which must be mixed with ethyl alcohol. Shellac would become an important ingredient for European lacquer imitations. French polishing, one of the traditional highest finishing method for Western furniture, is the technique in which shellac is applied in thin layers using tampons.

Linseed oil is a colourless to yellowish drying oil obtained from the dried, ripened seeds of the flax plant Linum usitatissimum. When it is heated to promote polymerization and oxidation, we are able to shorten the drying times.1

Owing to its polymer-forming properties, linseed oil is often blended with combinations of other oils, resins or solvents as an impregnate (primer), as a pigment binder in oil paints, as a plasticizer and hardener in putty, and oil finish or varnish in wood finishing.

Copal is an aromatic resin from trees, specifically the tree Protium copal Burseraceae. More commonly, copal is a semi-fossil of amber, containing a resinous material that is an intermediate stage of polymerization and hardening between gummy resin and amber. However, copal is quite a complex material:

Historically, all glass-like resinous substances were called "copal". Given the lack of botanical and chemical knowledge, nor the knowledge of the buyer or seller of the provenance of the product, it was almost impossible for them to tell whether the "copal" they were selling was a fresh resin, semi-fossilised of fully-fossilised resin. In case of a glass like fresh "copal" - like Langenheim defines it - this can be easily dissolved in ethanol and some other solvents. So heat is not required for fresh copal resins. On the other hand, the more polymerised the "copal" is - thus the older the copal sample is - the harder it becomes to be dissolved in a solvent. So heat becomes a requirement to break down the polymer chains and make it dissolve in a liquid. Both fresh copal and semi fossilised copal or fully fossilised resin (like amber) were used, but certainly for different purposes. Generally speaking, the more fossilized the resin, the more glossy the resin becomes, and the more durable the product will be against all weather conditions, making it suitable for exterior use.

Gum Animé: A name that has been given to several copal resins, usually soft, low, quality resins containing embedded insects or vegetation. Most often, anime refers to the resin obtained from the Hymenaea courbaril trees of South America. Confusingly, the name "gum anime" has also been used for the hard, semi-fossilized, high-quality Zanzibar copal. Animé has been used for making varnishes and scenting pastilles.2

By using purified gum lacq together with other ingredients such as sandarac, mastic and so-called white amber (i.e. an unspecified copal resin), lacquers used in japanning were usually prepared by mixing a number of materials. The materials listed below vary depending on each lacquer recipe, but were used in combination (mixed) with the resins listed above.

Gum Elemi: Manila elemi Canarium luzonicum, is one of the best known and is the single largest source of the world’s supply of elemi. Among the many species of Canarium in the Philippines, C. luzonicum is the only one that has been exploited commercially. Manila elemi had been exported from the Philippines in large quantities, particularly for preparing varnishes. The resin was not made directly into varnish but added to various spirit varnishes, making them less brittle and more plastic. Mixing elemi with copal, used for very hard finishes, made melting the copal much easier as well as giving a paler and more brilliant varnish.3

The essential oil, distilled from Manila Elemi, is also used for fragrance applications.

Benzoin/benjamin: Storax and Styrax are sometimes used synonymously in the literature, however, which unfortunately can result in confusion regarding the botanical source of the resin. Resin from Styrax is called gum benjamin, and the most commonly used resin from Asian species is known as benzoin.4

It is used in perfumes and certain types of incense for flavouring and medicinal purposes, and in alcohol varnishes to achieve greater brilliance and improve the smoothness of the layers of varnish.

Mastic: Pistacia lentiscus, with several described varieties, has been the most important producer of mastic, is a widely distributed dioecious (separate male and female plants) shrub or small tree, occurring in coastal areas from Portugal and Spain to Greece, Syria, and Israel as well as North Africa, in Morocco and Tunisia. Mastic has been extensively used in the manufacture of high-grade varnishes of pale colour to protect oil and watercolour paintings. For this purpose, it has the great advantage of being easily removed, either by solvents or friction, without damaging the painting. The gelatinous material known to artists as megilp, used in mixing oil colours, consists of a mixture of mastic, turpentine, and linseed oil. Mastic has also been used in lithography for retouching negatives and in cements for precious stones.5

Rosin is the resinous constituent of the oleo-resin exuded by various species of pine, known in commerce as crude turpentine. The separation of the oleo-resin into the volatile oil (spirit of turpentine) and common rosin is accomplished by distillation. The turpentine oil is carried off at a temperature of between 100℃ and 160℃, leaving fluid rosin, which remains at the bottom of the distiller and purified by passing through straining wadding. Rosin varies in colour, according to the age of the tree from which the turpentine is drawn and the degree of heat applied in distillation, from an opaque, almost pitch-black substance through grades of brown and yellow to an almost perfectly transparent colourless glassy mass. Rosin was mainly the basic ingredient of the Cremonese varnishes of the golden age cooked together with linseed oil. Another use of rosin, players of bowed string instruments apply rosin on their bow hair so it can grip the strings and make them vibrate clearly.

Gum Arabic (gum acacia, gum sudani, Senegal gum and by other names) is a natural gum originally consisting of the hardened sap of two species of the Acacia tree, Senegalia senegal and Vachellia seyal. The gum is harvested mostly in Sudan (about 70% of the global supply) and throughout the Sahel, from Senegal to Somalia. The name "Gum Arabic" was used in the Middle East at least as early as the 9th century. Gum Arabic first found its way to Europe via Arabic ports, and so retained its name. When it absorbs water, it swells like gelatin.

Isinglass size: Some recipes in Stalker & Parker's book call for Isinglass size. Isinglass is an adhesive obtained from the swim bladder of sturgeon fish. The swim bladders are to be dried. Collagen can be extracted by soaking small pieces in water and warming them to about 60℃, which then needs to be strained before use. In white coloured lacquers, it is used to mix Isinglass size with lead white6 pigment. In blue coloured lacquers, it is used to mix smalt7 pigments. The reason they used Isinglass size is to ensure that these light coloured lacquers are not affected by the colour of the binding medium. For this purpose, Gum-water8 was also used.9

Venetian turpentine: See Rosin for details. It was said to be of the highest quality among turpentine spirit. Like the recipe (Stalker and Parker) says; ‘Then with a quarter of a pint of the thickest seedlac mix of Venice turpentine the bigness of a walnut and shake them together until it is dissolved’. Thus, Venetian turpentine was mixed into the thick seedlac and strain it afterwards; Venetian turpentine was used as a solvent.10

Gamboge (yellow): Resin from Garcinia has been collected from several species in Thailand, Cambodia, and other parts of Southeast Asia for varnish, a colouring agent, and at one time, medicine, because of antibacterial properties. The yellow resin is collected from spiral incisions in the bark; after half-set, it is pressed into cakes that are sold. It has also been used in China since the 13th century for making a golden spirit varnish known as pear ground (Nashiji-like) for coating metal, the lacquer built up in layers with each layer sprinkled with gold dust.11

Dragonblood (red): Dragon's blood brings to mind the image of an alchemist preparing various magical potions in a medieval castle. In fact, this name has been used in some form or another since ancient times to refer to a blood-red resin. In Roman times, it likely came from drops formed by the natural exudation of Dracaena cinnabari found on the isle of Socotra. By the 15th century, resin began to be collected from the stems of Dracaena draco in the Canary Islands.

It is not clear when they started to use the resin harvested from the exterior sheath on the fruit of Daemonorops draco, a rattan palm that grows in Borneo, Sumatra, and Malaysia.12

Saffron (yellow) is a spice derived from the flower of Crocus sativus, commonly known as the saffron crocus. The vivid crimson stigma and styles, called threads, are collected and dried for use mainly as a seasoning and colouring agent in food, contributes a luminous yellow-orange colouring.

Cochenille/Carmine (red): Cochenille or Carmine dyestuff is mostly used for precious decoration. The confusion is that the two names were frequently used as a synonym for each other whereas the two differ from each other. The Cochenille is dyestuff extracted from the Cochenillelous Dactilopius coccus. Carmine is a lake pigment13, coloured by Cochenille dye.14

Aloe (brownish colour with yellow tint) is a thickened juice of the leaves of different types of the Lilacaceae group and could act as a resin. It is listed as a mixing agent in William Salmon's yellow lacquer recipe.15

-

All varnishes or oil lacquers can make use of fresh/boiled linseed oil and stand oil (polymerised linseed oil), and will produce an oil varnish or an oil lacquer. The benefit of using boiled linseed oil or stand oil is that both boiled linseed oil or stand oil is already half-way polymerised. The downside is that both are way more viscous then freshly pressed oil, which also influences your varnish/lacquer mixture’s viscosity. Depending on the object and the application methodology, you might not - or contrary - want to increase your mixture’s viscosity. ↩

-

CAMEO; Conservation & Art Materials Encyclopedia Online, developed as a materials database in 1997 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. ↩

-

Jean H. Langenheim, "Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany", Portland, Timber Press, 2003. Pg. 356-357. ↩

-

Jean H. Langenheim, "Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany", Portland, Timber Press, 2003. Pg. 347. ↩

-

Jean H. Langenheim, "Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany", Portland, Timber Press, 2003. Pg. 385-388. ↩

-

Lead white is a thick, opaque, and heavy white pigment composed primarily of basic lead carbonate, with a crystalline molecular structure. It was the most widely produced and used white pigment in different parts of the world from antiquity until the nineteenth century, when it was displaced by zinc white and later by titanium white. ↩

-

Cobalt glass known as smalt when ground as a pigment, is a deep blue coloured glass prepared by including a cobalt compound, typically cobalt oxide or cobalt carbonate, in a glass melt. ↩

-

Gum Arabic dissolved in water. ↩

-

Marianne Webb, Jonas Veenhoven, "Recreating Western Lacquer using Historic Recipes" 2013. ↩

-

About the reason why it had to be "Venetian" turpentine, Ms. Marianne Webb, who recreated western lacquers using historic recipes, considers as follows:

‘Venice turpentine probably causes a softer varnish and gloss may by this fact decrease. On the other hand, the harder seedlac may form cracks over time due to its brittleness’. ↩ -

Jean H. Langenheim, "Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany", Portland, Timber Press, 2003. Pg. 381-382. ↩

-

Marianne Webb, Jonas Veenhoven, "Recreating Western Lacquer using Historic Recipes" 2013. ↩

-

A lake pigment is a pigment made by precipitating a dye with an inert binder, or mordant, usually a metallic salt. Unlike vermilion, ultramarine, and other pigments made from ground minerals, lake pigments are organic. ↩

-

Marianne Webb, Jonas Veenhoven, "Recreating Western Lacquer using Historic Recipes" 2013. ↩

-

Marianne Webb, Jonas Veenhoven, "Recreating Western Lacquer using Historic Recipes" 2013. ↩