European lacquer

by Vincent Cattersel

General Introduction

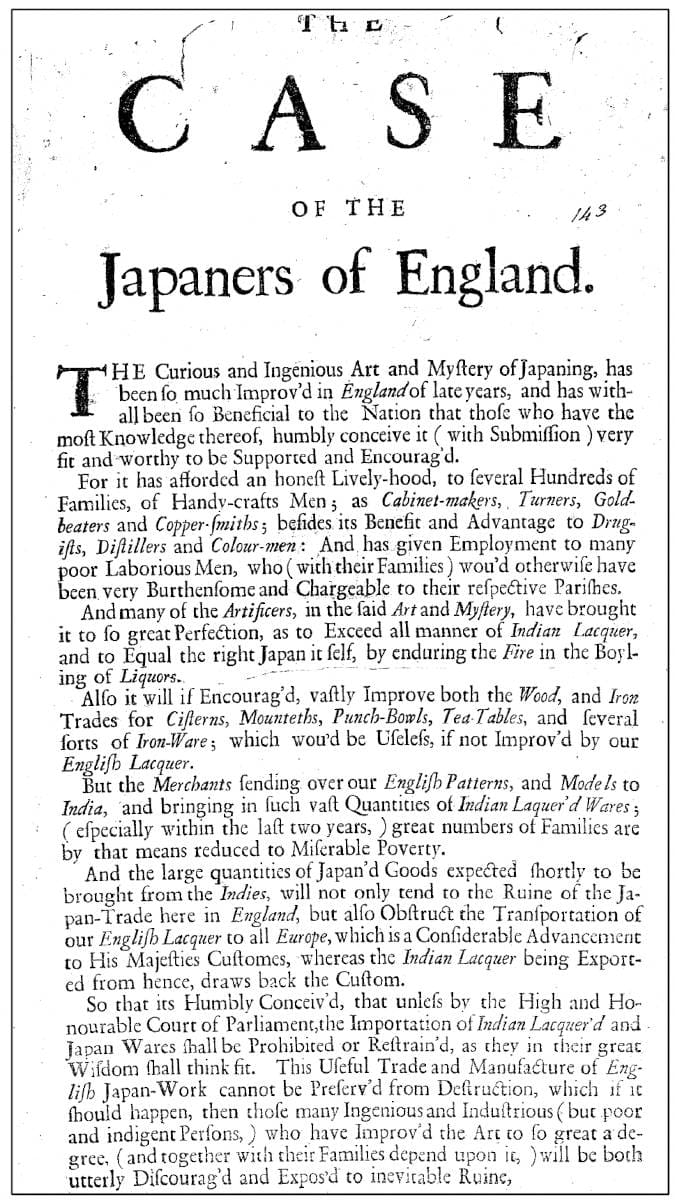

The foundation of the history of the European lacquering tradition is tied to European trade with the Far East. Through the import of Far Eastern lacquerware via important trade hubs such as the ports of Venice and Amsterdam (Dutch East India Company), Chinese and Japanese lacquer wares made their way to Europe at the start of the 16th century. The exotic aspect, with its high-glossy surface and decoration in sprinkled gold, and the near-mythical properties of Eastern lacquer, were new and fascinating to Europeans at the turn of the 17th century. Due to its rarity and the appeal of its unique material characteristics, Oriental lacquer was considered an exclusive commodity. Throughout the 17th century, Oriental lacquerware became embedded in the social status and domestic pride among the elite and aristocracy in Europe. Not only its intrinsic materiality but also the origin of the raw material sparked fascination and experimentation among European artisans. Art technical information and the physical features of the raw materials and Eastern lacquerware were first disclosed through the printed travel accounts of the Italian Jesuit Martino Martini (1614-1661) and the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1601/1602-1680). European artisans were not able to recreate Eastern lacquerware; not only did they have limited or no access to the raw lac ingredients, but they also had little notion about the production techniques and curing processes. In 1771, Delormois prompted the idea to commercialize the raw Eastern lacquer resin in Europe by importing and cultivating the trees, with the imagination of having unrestricted access to the Far East's raw lacquer material. He, however, added that he was still looking for someone who would embark on this concept and find a proper climate to grow the lacquer-providing trees on the European continent. Delormois then concluded that it is more ‘natural’ to search for and experiment with a technology that would imitate the quality and properties of Eastern lacquers with available materials and techniques in Europe. Reverting to known materials and techniques is precisely what the European artisans did, first 170 years before Delormois' statement and in a second ‘wave’ around the mid-16th century. Imitation through innovation was Europe’s answer to the influx of imported lacquerware. Innovation, since both the materials and the techniques, were already at hand from the art of varnishing; an established technology at the turn of the 17th century. Hence, early 17th-century European artisans experimented with materials and techniques that could replicate the intrinsic characteristics of Eastern lacquerware; decorated objects with a flawless and highly glossy coating and contrasting gold decorations. The constant flood of imported lacquerware was needed to fulfill the high demand to such an extent that it would disturb the domestic European lacquer production and markets during the 17th and 18th century. The aforementioned is reflected by a petition filed with the British Parliament requesting the control of imported lacquerware in 1692 London. A reprint of this one-page petition from 1701, titled ‘The Case of the Japaners (sic) of England,’ was filed by the guild(like?) organization ‘Company of Patentees for Lacquering after the manner of Japan.’ This document not only reveals a rare glimpse into what appears to be an already well-established (imitation) lacquering industry in London at the end of the 17th century, but it also marks the increasingly tense and competitive market situation of that time (Fig. 1).

The document addresses the wide variety of affected businesses and families who are buckling under the economic losses due to the vast import of Eastern lacquerware (Indian Lacquer and Japan Wares). A whole supply chain relying on European lacquer making was affected by these imports, including distillers, druggists (apothecaries), and color merchants (pigment and paint material traders). It demonstrates that there was an economic drive to counter the ever-increasing demand in Eastern lacquerware to protect domestic production. Although economic aspects indeed were at stake, the collective artisans’ and the general public’s fascination had initially motivated them to imitate the exotic and unique characteristics of Far Eastern lacquer coatings and decorative techniques. Not surprisingly, the earliest surviving evidence of the art of imitating Eastern lacquerware originates from Amsterdam. Amsterdam, as one of the earliest trade hubs for Oriental lacquerware, provided artisans with direct (visual) and possibly hands-on access to imported lacquerware. Hence, they were able to observe and gather unprecedented insights into the construction and the physical appearance of Eastern lacquerware. In 1609, the Amsterdamian Willem Kick and his partners were granted a patent to produce ‘all sorts of lacquerworks (…) after those imported from Eastern India.’ The oldest surviving examples of Kick’s workshop or collective demonstrate that artisans were already successfully mimicking Eastern lacquerware during the first quarter of the 17th century (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

The technology used during the first quarter, and by extension, the first half of the 17th century, is still largely shrouded in mystery. Little research exists on the rare surviving lacquerware from this period. One paper by two Dutch researchers, Baarsen and Hagelskamp, is the only known study to our knowledge that analyzed European lacquer coatings from this early period. The analysis showed the lacquer was composed of a drying oil mixed with colophony (Pinus sp.) or Venetian turpentine (Larix decidua). The rarity of early 17th-century lacquers is in part reflected in the surviving written and printed evidence, which is, to our knowledge, non-existent for Northwestern Europe for the first half of the 17th century. Kircher (1667, Amsterdam) and De Sylva (1670, London) are considered one of the oldest surviving sources revealing technological aspects of the making of European lacquers. These were published nearly 50 years after the earliest surviving examples of European lacquerware by Willem Kick (first quarter 17th century). Eighteen years later, in 1688, Stalker and Parker published the oldest known treatise entirely devoted to the art of japanning and varnishing in Oxford. In that same year, Margravine Sibylla Augusta of Baden-Baden (Prussia, Germany) wrote a personal manuscript with a list of European lacquer recipes. From the first quarter of the 18th century, the number of written sources mentioning lacquerware increased significantly across Europe and demonstrated that both the interest and the techniques were well accustomed and deeply embedded in European society.